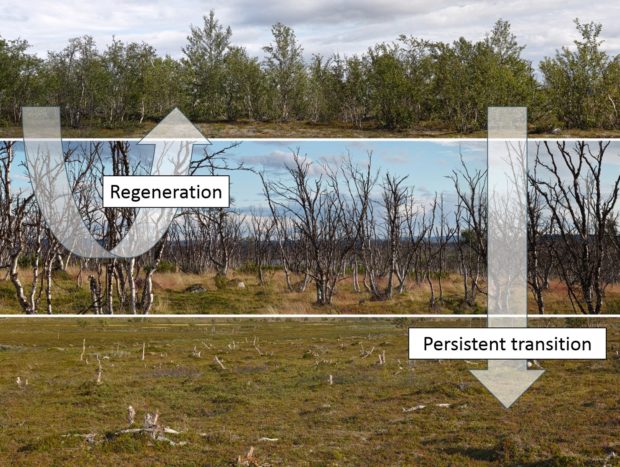

The effect of reindeer grazing on the assemblage of ground-dwelling spiders was studied along the Finnish-Russian border fence on lichen dominated pine heath. Changes in species richness, abundance and evenness of spider assemblages were analyzed in relation to changes in vegetation and environmental factors in long term grazed and ungrazed sites, as well as sites that had recently switched from grazed to ungrazed and vice versa. Grazing was found to have a significant impact on height and biomass of lichens and other ground vegetation. However, it seemed not to have an impact on the total abundance of spiders. This is likely caused by opposing family and species level responses of spiders to the grazing regime. Lycosid numbers were highest in grazed and linyphiid numbers in ungrazed areas. Lycosidae species richness was highest in ungrazed areas whereas Linyphiidae richness showed no response to grazing. Four Linyphiidae, one Thomisidae and one Lycosidae species showed strong preference for specific treatments. Sites that had recovered from grazing for nine years and the sites that were grazed for the last nine years but were previously ungrazed resembled the long term grazed sites. In the long term ungrazed sites we found both spider and plant species typical of peatlands living among the thick Cladonia lichen mat on the sandy soil.

The results emphasize the importance of reindeer as a modifier of boreal forest ecosystems. The sites with reversed grazing treatment demonstrate that recovery from strong grazing pressure at these high latitudes is a slow process whereas reindeer can rapidly change the conditions in previously ungrazed sites similar to long term heavily grazed conditions.

You can read the full article here.

Reference: Saikkonen T, Vahtera V, Koponen S, Suominen O (2019) Effects of reindeer grazing and recovery after cessation of grazing on the ground-dwelling spider assemblage in Finnish Lapland. PeerJ 7:e7330

Picture: Fence separating a grazed and an ungrazed site in Finnish Lapland (photo: Otso Suominen, University of Turku)